By Heather L. Johnson

Cypress, TX. 1985

I was one of those awkward suburban girls trapped by geography, hormones and the grave misunderstandings of my football-playing, skin-tight designer jean-wearing peers. I took it all out on my bedroom walls, pasting up cutouts of hot young boys from TEEN magazine and hair band musicians with cucumbers in their pants, abject byproducts of an extreme desire to fit in. There was always something missing, some chasm lacking form or language keeping me from becoming that carbon copied Barbie Doll I thought I was supposed to be.

Then a few things happened. Glorious things revealing a gorgeous yet hideous underside of life that rang true. My mother gave me her old car (a necessity in 80’s era Houston, when taking the bus meant a four-hour round trip to anywhere). With that came access to new experiences and ideas…and to a tribe of people unafraid to live fully, read between the lines and make art about what they found there.

This is how I first found Mydolls, a Houston-based, nearly all-female punk band that had been playing since 1978. Though they’d stopped performing by the time I was old enough to see them, their spirit had imprinted upon the Houston underground music scene to the degree that even random kids from distant suburbs were inspired by them. Their sound, an explosive mix of Au Pairs, the Slits, X-Ray Spex and early Siouxsie and the Banshees influences, was layered with something else – something hilarious but deadly serious, cutting yet colored by a love and self-respect that could only spring from the familial, from friendship bonds so tight each person finishes the other’s sentences. A “something else” springing from the obstinacy required to thrive in mid-80’s Houston, in all of its swampy, concrete, billboard grazed, freeway-strangled, police-brutality tainted glory.

Mydolls’ very existence helped me find and fight for my own voice as a young girl. The title of their collection, “A World of Her Own” (a compilation of singles and early material released in 2007) couldn’t express that more clearly.

Still together after 39 years, all four original members have granted us theirs.

* * * *

When I think of Houston in 1978, I try to imagine it prior to the Reagan years, but at the height of the cold war. The oil industry there was booming; disco and stadium rock filled the top-40 airwaves. How did you find each other and what motivated you to start a band?

TRISH HERRERA (VOCALS/GUITAR): The Texas scene was small. We found each other through innate recognition. No one said, “Hey, I hate Reagan, let’s start a band.” We just knew that together we could be a voice and we all had the same drive for disruption and change.

GEORGE REYES (DRUMS): I think there was a lot going on pre-Reagan. The police were out of control in Houston. So it was a real shock to see [Trish’s] cousin’s picture in Time magazine related to the police and the repression they dealt out during the 1970s. The Moody park riots were also a reaction to police brutality.

DIANNA RAY (BASS/VOCALS): The physical genesis of the band came from Trish and myself, but the impulse that drove it started many years earlier for me. I love all forms of art, something my mother gifted me, but music draws my most visceral response. I was a loner kid with a rich interior life; music became my companion. Years later, Trish and I were seeing shows at the Island, Houston’s only punk club back in 1978, and one day we were standing in front of the stage after a band had finished. Impulsively, we decided to form one. We knew a lot of people playing music and it seemed natural.

LINDA YOUNGER (GUITAR/VOCALS): Divine Providence…I felt it then and I feel it now. There was a reason we met, formed a band and stayed together for all these years. The story continues to unfold.

What were you all listening to and thinking about that underscored this motivation?

TH: We didn’t agree with the general population’s apathy toward politics, war, attacks on LGBT or women’s rights. Using religion to back up hate was starting to become an American past time.

GR: Seems like there was global unrest. The news was always bad and the music we were listening to reflected economic and political malaise.

DR: I can’t say I had a conscious political motivation when we first started, though that quickly surfaced. I was emotionally gutted by the Vietnam War, which heavily influenced my social and political beliefs. Having come from Michigan, where music was almost a religion, I was introduced to Iggy and the Stooges, The New York Dolls, Patti Smith and The Ramones. Then came post-punk. What a revelation that was! Au Pairs, The Raincoats, the Slits, Lora Logic, PIL, Joy Division, The Pop Group, wow!

LY: I have always listened to a wide variety of music and still do, but Flipper, Iggy Pop and the Stooges, Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, The Raincoats, the Slits, Siouxie and the Banshees and the Cramps were some of my faves at that time.

Was there anything in particular about Houston that made you make and perform “disruptive” music?

TH: Anger and a desire to bring attention to political and social issues was fueled into song and performance. It was just the next step for us.

GR: I think Joe Campos Torres’ death really galvanized a segment of Houston, while the rest of the city was enamored with Gilley’s and “Urban Cowboy”.

DR: I have to agree with George on how galvanizing Joe Campos Torres’ murder was. He was a 23-year-old Vietnam veteran murdered by six Houston Police officers. They beat him and pushed him into the bayou where he drowned. His body was found two days later. Two of the officers were tried for murder and found guilty of negligent homicide. They received one year of probation and a $1 fine. It was an insult. The sentencing sparked riots in Houston’s Moody Park, crystallized and personalized divisions between ordinary citizens and those in power. It was time to push back.

LY: Sadly, what makes our music timeless are these recurring events. Racism, sexism, police brutality…. Clubs like the Island provided safe havens, where freedom of expression was embraced. And much of that was in the form of angry, fast, loud music.

During the early 80s you guys toured around the country, appearing in Wim Wenders’ film “Paris, Texas”, and more. What made you stay in Houston rather than relocate to LA, NYC or even Austin, for a bigger chance at financial success or notoriety? What was at the center of this experience for each of you?

TH: Punk was a boys’ world in the big picture. Although our local punk men supported us, women were generally still front singers with cute gimmicks. Three women dressed in black, shouting and pointing out social misnomers and political injustice was not popular.

GR: I don’t think financial success or notoriety played a big part in our decisions. We wanted to share the music with larger audiences but not at the expense of creativity. Linda’s interview with John Peel on BBC Radio really expresses what we were about. I love Peely’s comment on “the demands of the audience.” We play what we want to play and let the audience find us.

DR: We had a pretty great scene going on in Houston. It was a vibrant mix of music, artists, fashion and politics. I’d call being able to live and play music with the likes of Really Red, The Degenerates, Legionaries Disease, The Dicks, The Big Boys, Butthole Surfers, Culturcide, artists like Mel Chin, Jack Livingston, James Surls, and William Steen pretty damn successful. Cultural currency was way more important than dollar currency.

LY: I think we each have different reasons why Houston is home for us. For me, it’s family and friends. Our recent performances at Lawndale Art Center (formerly Lawndale Art Annex) and Contemporary Art Museum Houston brought “our Tribe” together to celebrate our musical journey in a way that just can’t be described in words. It was a feeling of unconditional love, total acceptance and appreciation for our legacy. We’re currently working on a documentary with Cressandra Thibodeaux and 14 Pews, and I am blown away by the incredible footage of us at various performances, practicing with Amos, Dianna’s dog (our howling back up on the song “Politician”), and all the interviews being conducted. Much more to come on that labor of love.

Fears of a nuclear apocalypse permeated so much of our culture during the early/mid 80’s; I remember its possibility creating a constant tension, bleeding into films, music and television to the degree that it affected the tone of everyday life. How did that influence your choices of what to write, play and record during that time, if at all?

TH: In the 80s, American Cruise missiles were being planted in our ally countries. The United States was becoming unpopular all over the world for our mongering. We felt that while traveling in England. It was and is never the people’s choice to go to war and kill our young men and women. The government decides that. This powerlessness and victimization afflicted by our own country created a ping-pong subculture starting with beatniks in the 50s responding to the Russian Commie scare. We fight back with words and song; we are responsible to speak up.

GR: Anarchy was a big theme, although not too many people knew what that was. You could still discount people’s views by calling them “Commies”, but anarchist, what the hell was that? It really was underground. I recall having to use a secret password to get into the Anarchist Press in London. These experiences came out in our music. The marching snare in “Politician” and the apocalyptic guitar riffs demonstrate how much chaos was surrounding us.

DR: I was more influenced by actual bombs going off in Northern Ireland and Beirut, the insane violence of religion in these countries and in South America with the Jonestown Massacre. How religion was used to manipulate, oppress and separate people. Those are some of the thoughts that came out lyrically in our song, “Soldiers of a Pure War.”

LY: It makes me sad that things seem to be heading in the same direction with regard to nuclear threats and the “bullying” mentality permeating the air right now. At least we know that “Duck and Cover” is not going to protect us anymore.

How did the rise of hardcore affect your music? Did the audience change, and did they remain receptive to you? Did it transform your own attitudes toward performing?

TH: There is a degree of disconnect. Some feel punk is kid stuff and don’t participate anymore. Those people may be living more conservative lives but are still punk rock in attitude. Mydolls audiences range from five-year-olds to 105-year-olds — it’s crazy but we seem to have a vast appeal like that.

GR: I recall Bob Weber’s 50-something uncle coming to a Butthole Surfers show we were performing, who really got into slam dancing. Hardcore was out there along with a lot of other creative expression. Audiences react to what’s on stage. They’re not too picky when something engages them.

DR: I think the hardcore scene had a more profound effect on me as an audience member than as a musician. I enjoyed the playful skanking and moshing we did before the really young hardcore boys hit the scene; after that it became very aggressive in the pit. I weighed 100 lbs and couldn’t compete with someone twice my weight, all muscle and not looking out for me. Early on we took care of each other. If you started to fall, someone was there to pick you up before you even hit the floor. No one was rough – it was playful and joyous, even during the hardcore shows.

I will say this – at a recent show here in Houston I watched you, Heather, crouched in front of the stage taking photos, and a gentleman scooted right in behind you and kept the moshers back so they wouldn’t hurt you. I thanked him afterwards. I’d like to see more of that! We can all have fun and do it in a way that is respectful and allows everyone to be engaged.

LY: Our music has a hardcore message delivered a little differently. The punch is more subtle, almost poetic. I think the music and audience always evolve. The attitude to encourage others to “Go Make a Band!” remains.

Mydolls audiences start earlier than five-year-olds. My granddaughter, Molly, has been a Mydolls fan since infancy. She is three now and recently performed live on stage with us at Cactus Music, a local record store in Houston. She loves practicing “Totally Wired” [Mydolls’ cover of a song by the Fall] and is a constant reminder that we have a moral responsibility to keep our message loud and clear, and to pass the baton to the next generation. We nurture our future hardcore performers while maintaining love and respect for those who have been with us from the beginning. We met a whole new generation of hardcore punks at “Take This Fest and Shove It” [a music festival featuring mostly Houston and Texas-based bands that occurred April this year]. It reinforces the need to keep playing and to support others in performing as well.

You have been, for all 39 of your years, a mostly female band, operating in a very male-dominated music scene. Is this something you all were conscientious of, and if so, what gave you the guts to dive in?

TH: I don’t think we really thought about our femaleness at that point. We were just doing it.

GR: I don’t know if it was the personal connections with male musicians or that women’s music was developing, but our reception was very positive. I can’t recall that we labored over conscious considerations of being dominated by a scene. That might have to do with the fact that we were focused on creating music and not worrying about who headlined. We still think that way. We’re just happy to be there and play.

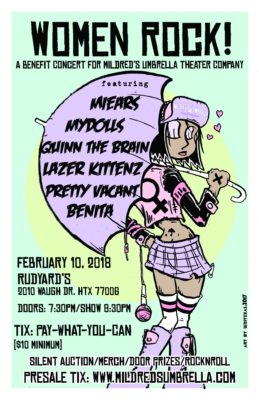

DR: It was probably more naiveté than guts. We looked for a female drummer before we found George, so our original intention was to be an all-female band. It was more of a novelty back in the ’80s than it is now. Thankfully there are so many more gender-integrated bands these days that we’re almost at a place where we don’t single people out for special attention based on their gender. We aren’t there yet. That is one of the reasons we’re involved in the Girls Rock Camp organization. We want to see more women pick up instruments, learn how to run sound, write songs, form bands and book shows. We also have a new female collective in Houston that books shows, supports one another’s creative endeavors and keeps venues safe for women, called DAMN GXRL. Female audience members and performers experience a shockingly high amount of sexual inappropriateness from industry people and audience members. That really needs to change – for Christ sakes, it’s 2017! It’s called R-E-S-P-E-C-T. We’re a tribe and we take care of each other. Predators have no place and should be called out for their behavior.

LY: It was not on my radar screen. Sexist promoters and club owners asking for men to collect our money at the end of nights did piss me off and bring the issue to the forefront. I am very supportive of the current movement in Houston to address that.

What was your first show like and how were you received?

TH: We opened for the Hates at the Parade Disco and were not afraid at all, but our hardcore punk male supporters were a little nervous for us. Thanks to the kindness of the Hates we had a very successful show and were launched into the world with a lot of positive reception.

GR: I think this show was part of an early Gay Pride Week performance. Again, I think we were happy to put the hours of practice into a performance. I lost my wedding ring at that show which may have been a sign on the direction I was taking and that of the band.

LY: The Hates welcomed us and we are grateful to Christian Kidd for that. We continue to experience that kindred spirit with them to this day. We are currently involved in fundraisers to pay it forward now. Christian is battling cancer, as are many of our fellow musicians and friends. The punk rock community is incredibly supportive, and so many have stepped forward to raise money to help him with medical expenses. We stand with them. Oh Cancer, Up Yours!

GEORGE, what was it like to be the only guy in the band?

GR: Having already played in garage and cover bands, I came to Mydolls with a music background. Working with novices playing instruments and performing really minimized the ego-tripping I had experienced with other performers. I had to check my own ego in learning how to play with people who were totally focused on creating music and expressing themselves rather than developing an aura of stage presence. It’s been interesting, especially on the road. I’ve adjusted to the time element (make up, wardrobe, etc.) and have found opportunities to explore and write.

Were you all initially accepting of one another’s musicianship, tastes, etc… or were there growing pains?

TH: We were all just having fun; we barely have tension. If it happens, it’s just slight irritation about not being on the same schedule.

GR: Since this was definitely a DIY formation, I would say that we all learned together. I accepted the recommendation to change from ride cymbal to floor tom rhythm. It has become signature to our music. I think as we have been out of sync from time to time, the irritation has been channeled into better performances.

DR: Well, I had no experience playing a stringed instrument, nor any ability to read music, but I loved it and that was enough to start. The band made adjustments along the way. When we started we had a keyboard, which we dropped pretty quickly. We gave George a really hard time about playing too much snare and cymbal combos. We just kept telling him to hit the toms! He accepted the challenge of doing things differently, opening up as a drummer. He makes playing bass a lot of fun. In fact I think he makes me a better bass player.

Though we shared musical interests, we had different influences. Those differences helped us develop our own unique sound.

LY: We continue to challenge each other with the music, and this only makes it better. The fact that we have remained a band for so many years is a testament to our mutual respect and encouragement.

Jumping forward to 2008…what inspired your re-emergence after a 13-year hiatus?

TH: Dianna and I had been playing in bands all along, and Linda and George had taken some time off to have and raise children. It just seemed the next step. I was very disturbed by some of the legislation for LGBT rights and we talked a lot about that in 2008. Kathy Johnston was a miracle in helping us organize and pull together a full set and play some shows.

GR: I recall that there was a birthday party Mydolls was requested to play. I know we wanted to present a good performance, so we organized some practices, dusted off some songs from our playlist and have been playing ever since.

DR: In 2008 we were asked by Anna Garza and Rosa Guerrero to be a part of “Noise and Smoke 2”, a festival they and Liz Molina put together. That was about a year after we released the anthology double CD, “A World of Her Own”. The timing felt right and they were so sweet and earnest that it was impossible to say no.

Then we just kept at it. Kathy Johnston was playing with us as she had at the very end of our 1980s performances. She had a great ear, helped us relearn our material and added depth to our songs. Unfortunately we lost her to blood cancer back in 2011. Sometimes, in her honor, we set an empty chair for her on stage. I miss her every day.

How had Houston changed and how had the punk scene there and in Texas changed? How did your voice as a band shift with age, and with the times?

TH: The growth of Houston has affected small clubs and the independent music scene; the digital world has created a free market for music. So basically the only way independent bands make money is by selling records at shows or in independent cool record stores. (A shout out to all those stores who help us, and a special shout out to clubs gibing us guarantees and support!)

We have had to learn to ask for payment, which is really hard when you grow up in a free thinking punk rock world with a disdain for success. All our money pools back into recording and touring.

GR: As times have changed, so have we. There are more Houston venues and a greater opportunity to perform to a larger audience. We played at the Houston Library last summer. We definitely have had to adapt to the electronic, social media world. I think as far as shifts go, we’re building a legacy for girls and women to express themselves. And for the punk rock world, we continue to be a model of that same self-expression.

DR: Houston’s population had grown exponentially in the years we were on hiatus. Social media was on the rise, translating into an even more diverse audience, especially as it pertained to age. One of the things about punk rock that amazes me is its power to endure. With the Internet more young audiophiles everywhere have learned about obscure bands like ourselves. They share playlists and information, creating new audiences. I think we were very lucky to have lived during the first and second waves of punk, but the younger kids today are every bit as excited and innovative in their approach to music. They are also very supportive of each other’s bands across genres.

When I was in my 20s I was more concerned with my image and how cool I was on stage. Now I just want to have fun, play music and pass out an abundance of hugs to friends in the audience, onstage and in other bands. We recently attended and played a festival called “Take This Fest and Shove It!” You were there Heather, and it makes me so happy to see how many we used to play shows with still making music well into their 50s and 60s. Punk music. I think it keeps us young. We have found the fountain of youth!

LY: We have learned the value of good dialogue before agreeing to play, and we make sure that compensation and equipment availability are clear up front. Older and wiser, we recognize the need to have someone like Nancy Agin Dunnahoe with Neon Artifact and Wild Dog Archives as our press agent, who keeps us focused with our “Eye on the Prize.”

And now… you’ve just released a new record, “It’s Too Hot for Revolution,” in one of the strangest moments of modern times, with an unpopular “strongman” in the presidential seat, whose actions and policies are bringing about renewed fears of nuclear war. At the same time, I’ve witnessed an unbelievable spirit of love and optimism emanating from people who attend your shows, who range so greatly in age. What are your hopes for this new album in terms of how it will be received by this new/old audience?

TH: “It’s Too Hot for Revolution” is all about apathy. It’s about getting off our couches. Put down the remotes and phones and get out to some shows. Mydolls rails against the puppet and we hope for goodness and fairness in our future.

GR: I think we are hoping it motivates people to action. The lyrics to the title cut offend many groups, laced with micro-aggressions for several. I think in today’s climate, there is a great need to be intentional and deliberate. I’m glad that love and optimism are being spun at our shows but I think we’d like to see a counter to apathy.

DR: We’re really proud of the record; it was a labor of love by many. One side is softer in its musical and lyrical tone. It has songs about love and personal struggles. One is especially personal to us: “Don’t Fucking Die.” It’s about cancer, which has and continues to affect each of us in the band through our own diagnoses and cures, as well as friends who are newly diagnosed and those we have lost to the disease. FUCK cancer.

The other side of the EP is more political and biting. Trish changes some of the words when we perform to better align with what is happening in the moment. Capitalism without morals will eventually consume itself. It feels like we hit a new low every day. I am hoping for a correction, even an over-correction towards love and acceptance – because tolerance isn’t good enough. We are a better people than our country currently reflects. That is why I still cling to the optimism you referred to in your question. The best antidote for hate is love. And hugs, lots and lots of hugs! And dogs too. Dogs are great.

LY: We have gotten such positive feedback on our new red vinyl release. This album spans years of Mydolls music and tells our story over time. It starts with incredible cover art by friend and creative genius, Jack Livingston. Insert contains the lyrics and a Mydolls self-portrait by Trish from 1989. The song selection represents earlier recordings by our very special sound engineer Phil Davis done in 1982 on reel to reel tape, lovingly restored by Dan Workman at SugarHill Recording Studios, and re-engineered by Andy Bradley at Wire Road Studios. It is a true labor of love and we are so proud of how well it turned out.

Finally…I’d love it if each of you share a story. Some moment that crystallizes what this band means to you. It could be an interaction with an audience member, a moment on stage, or a personal experience inspiring lyrics to a song…whatever comes to mind first.

TH: My favorite memory in the 80s is playing at the Island on Main Street when some of the ceiling tiles fell on my head. Kind of just says it all.

GR: Margaret Moser and I go way back to a different time and place in Austin. We both worked at a restaurant in the mid 70’s. Years later Mydolls played Raul’s on the drag. Other than a tire being slashed by frat boys, the evening started with Margaret coming back stage and identifying herself to me as a former workmate. She ended by saying “now I am a famous editor and you are a famous musician.” Didn’t think much of it at the time, but I guess we are.

DR: Music in general and playing it has literally saved my life. From times as a teen through my early 20s when I was suicidal, and recently while coping with the death of my wife and Mydolls’ guitarist Kathy Johnston, it has given me companionship, creative and spiritual connection to the Universe, and the ability to exist in the moment while letting everything else fall away. It has brought and kept the most amazing people into my life: people like you, Heather; my band mates in Mydolls; and those in the other band Trish and I play in, No Love Less.

Music forms a unique connection between the players, the thing itself and the listener. It is magical. A song can take us back to a specific time, place and feeling like nothing else. The notes become part of our DNA independent of whoever wrote it. I can’t imagine a better or more potent gift.

LY: My favorite memory is being interviewed on the John Peel BBC radio program in 1982. He was such an advocate and wanted to know all about Houston. I listen to the interview and smile at the questions and answers from the young, naïve Linda, and the warmth and wonderful sense of humor of someone we all loved and admired.

* * * *

Houston, TX. 2016

I left Houston in 1987, to return after 29 years. I’d lived in 7 different cities, and had just spent 10 months riding a motorcycle all over Latin America for an art project (appropriately called “In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful”) [https://www.facebook.com/TheFrighteningAndBeautiful/]). I was in a city I felt I no longer knew, once again without many friends.

One day I saw a listing for a free show at the Houston Public Library. It was a Mydolls show. “Holy shit,” I thought. “I finally get to see them play!”

Those four best friends owned the stage so completely and with such pleasure that all the good parts of Houston came flooding back that afternoon.

After their set, Trish walked right up to me and asked, “Who are you? Don’t I know you?” Then Dianna came over and gave me an enormous hug. Neither of them had in fact ever seen me before.

Who am I? I’ll probably be trying to figure that one out till I’m dead. But at least now, thanks in great part to this band, I have a solid clue as to where I belong.

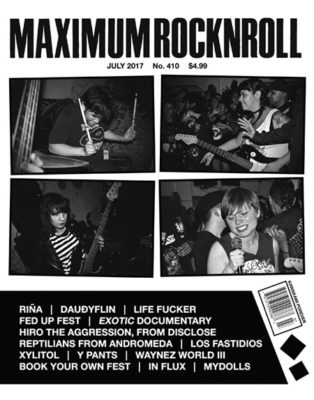

Source: MRR #410 July 2017

Artist page: In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful